Tech

Mathematicians are deploying algorithms to stop gerrymandering

Published

3 years agoon

By

Drew Simpson

For decades, one of those users was Thomas Hofeller, “the Michelangelo of the modern gerrymander,” long the Republican National Committee’s official redistricting director, who died in 2018.

Gerrymandering schemes include “cracking” and “packing”—scattering votes for one party across districts, thus diluting their power, and stuffing like-minded voters into a single district, wasting the power they would have elsewhere. The city of Austin, Texas, is cracked, split among six districts (it is the largest US city that does not anchor a district).

In 2010, the full force of the threat materialized with the Republicans’ Redistricting Majority Project, or REDMAP. It spent $30 million on down-ballot state legislative races, with winning results in Florida, North Carolina, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio. “The wins in 2010 gave them the power to draw the maps in 2011,” says David Daley, author of, Ratf**ked: The True Story Behind the Secret Plan to Steal America’s Democracy.

“What used to be a dark art is now a dark science.”

MICHAEL LI

That the technology had advanced by leaps and bounds since the previous redistricting cycle only supercharged the outcome. “It made the gerrymanders drawn that year so much more lasting and enduring than any other gerrymanders in our nation’s history,” he says. “It’s the sophistication of the computer software, the speed of the computers, the amount of data available, that makes it possible for partisan mapmakers to put their maps through 60 or 70 different iterations and to really refine and optimize the partisan performance of those maps.”

As Michael Li, a redistricting expert at the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University’s law school, puts it: “What used to be a dark art is now a dark science.” And when manipulated maps are implemented in an election, he says, they are nearly impossible to overcome.

A mathematical microscope

Mattingly and his Duke team have been staying up late writing code that they expect will produce a “huge win, algorithmically”—preparing for real-life application of their latest tool, which debuted in a paper (currently under review) with the technically heady title “Multi-Scale Merge-Split Markov Chain Monte Carlo for Redistricting.”

Advancing the technical discourse, however, is not the top priority. Mattingly and his colleagues hope to educate the politicians and the public alike, as well as lawyers, judges, fellow mathematicians, scientists—anyone interested in the cause of democracy. In July, Mattingly gave a public lecture with a more accessible title that cut to the quick: “Can you hear the will of the people in the vote?”

Misshapen districts are often thought to be the mark of a gerrymander. With the 2012 map in North Carolina, the congressional districts were “very strange-looking beasts,” says Mattingly, who (with his key collaborator, Greg Herschlag) provided expert testimony in some of the ensuing lawsuits. Over the last decade, there have been legal challenges across the country—in Illinois, Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin.

But while such disfigured districts “make really nice posters and coffee cups and T-shirts, ” Mattingly says, “ the truth is that stopping strange geometries will not stop gerrymandering.” And in fact, with all the technologically sophisticated sleights of hand, a gerrymandered map can prove tricky to detect.

JONATHAN MATTINGLY

The tools developed simultaneously by a number of mathematical scientists provide what’s called an “extreme-outlier test.” Each researcher’s approach is slightly different, but the upshot is as follows: a map suspected of being gerrymandered is compared with a large collection, or “ensemble,” of unbiased, neutral maps. The mathematical method at work—based on what are called Markov chain Monte Carlo algorithms—generates a random sample of maps from a universe of possible maps, and reflects the likelihood that any given map drawn will satisfy various policy considerations.

The ensemble maps are encoded to capture various principles used to draw districts, factoring in the way these principles interact with a state’s geopolitical geometry. The principles (which vary from state to state) include such criteria as keeping districts relatively compact and connected, making them roughly equal in population, and preserving counties, municipalities, and communities with common interests. And district maps must comply with the US Constitution and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

With the Census Bureau’s release of the 2020 data, Mattingly and his team will load up the data set, run their algorithm, and generate a collection of typical, nonpartisan district plans for North Carolina. From this vast distribution of maps, and factoring in historical voting patterns, they’ll discern benchmarks that should serve as guardrails. For instance, they’ll assess the relative likelihood that those maps would produce various election outcome —say, the number of seats won by Democrats and Republicans—and by what margin: with a 50-50 split in the vote, and given plausible voting patterns, it’s unlikely that a neutral map would give Republicans 10 seats and the Democrats only three (as was the case with that 2012 map).

“We’re using computational mathematics to figure out what we’d expect as outcomes for unbiased maps, and then we can compare with a particular map,” says Mattingly.

By mid-September they’ll announce their findings, and then hope state legislators will heed the guardrails. Once new district maps are proposed later in the fall, they’ll analyze the results and engage with the public and political conversations that ensue—and if the maps are again suspected to be gerrymandered, there will be more lawsuits, in which mathematicians will again play a central role.

“I don’t want to just convince someone that something is wrong,” Mattingly says. “I want to give them a microscope so they can look at a map and understand its properties and then draw their own conclusions.”

COURTESY PHOTO

When Mattingly testified in 2017 and 2019, analyzing two subsequent iterations of North Carolina’s district maps, the court agreed that the maps in question were excessively partisan gerrymanders, discriminating against Democrats. Wes Pegden, a mathematician at Carnegie Mellon University, testified using a similar method in a Pennsylvania case; the court agreed that the map in question discriminated against Republicans.

“Courts have long struggled with how to measure partisan gerrymandering,” says Li. “But then there seemed to be a breakthrough, when court after court struck down maps using some of these new tools.”

When the North Carolina case reached the US Supreme Court in 2019 (together with a Maryland case), the mathematician and geneticist Eric Lander, a professor at Harvard and MIT who is now President Biden’s top science advisor, observed in a brief that “computer technology has caught up with the problem that it spawned.” He deemed the extreme-outlier standard—a test that simply asks, “What fraction of redistricting plans are less extreme than the proposed plan?”—a “straightforward, quantitative mathematical question to which there is a right answer.”

The majority of the justices concluded otherwise.

“The five justices on the Supreme Court are the only ones who seemed to have trouble seeing how the math and models worked,” says Li. “State and other federal courts managed to apply it—this was not beyond the intellectual ability of the courts to handle, any more than a complex sex discrimination case is, or a complex securities fraud case. But five justices of the Supreme Court said, ‘This is too hard for us.’”

“They also said, ‘This is not for us to fix—this is for the states to fix; this is for Congress to fix; it’s not for us to fix,’” says Li.

Will it matter?

As Daley sees it, the Supreme Court decision gives state lawmakers “a green light and no speed limit when it comes to the kind of partisan gerrymanders that they can enact when map-making later this month.” At the same time, he says, “the technology has improved to such a place that we can now use [it] to see through the technology-driven gerrymanders that are created by lawmakers.”

You may like

-

Large language models aren’t people. Let’s stop testing them as if they were.

-

The Download: inaccurate welfare algorithms, and training AI for free

-

Successfully deploying machine learning

-

Generative AI risks concentrating Big Tech’s power. Here’s how to stop it.

-

Meet the AI expert who says we should stop using AI so much

-

Deploying a multidisciplinary strategy with embedded responsible AI

Tech

The hunter-gatherer groups at the heart of a microbiome gold rush

Published

5 months agoon

12/19/2023By

Drew Simpson

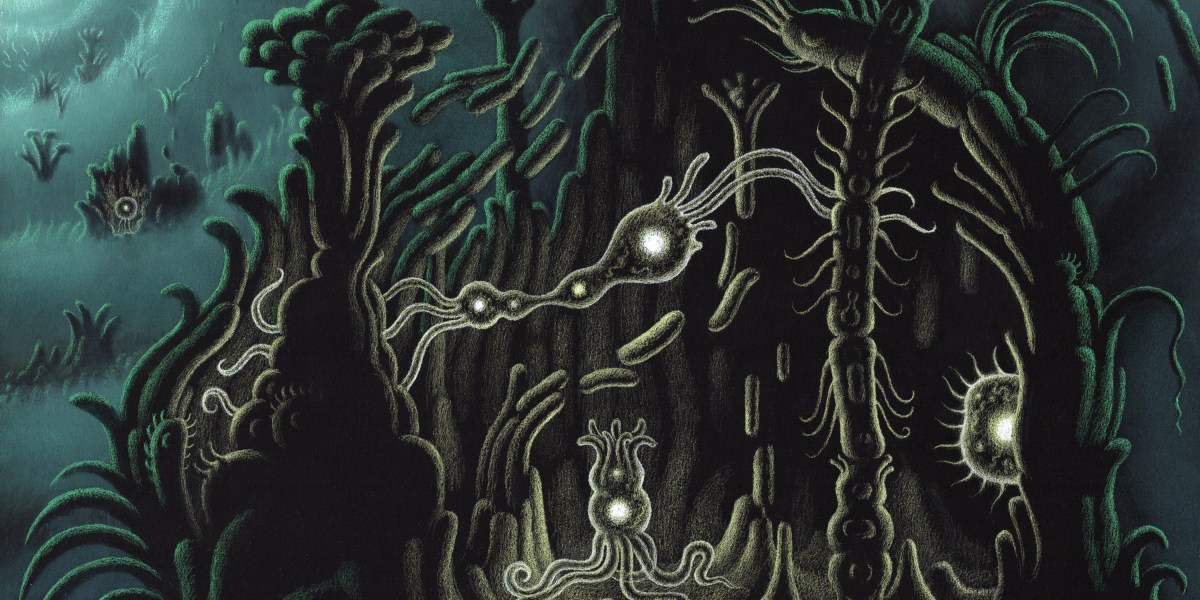

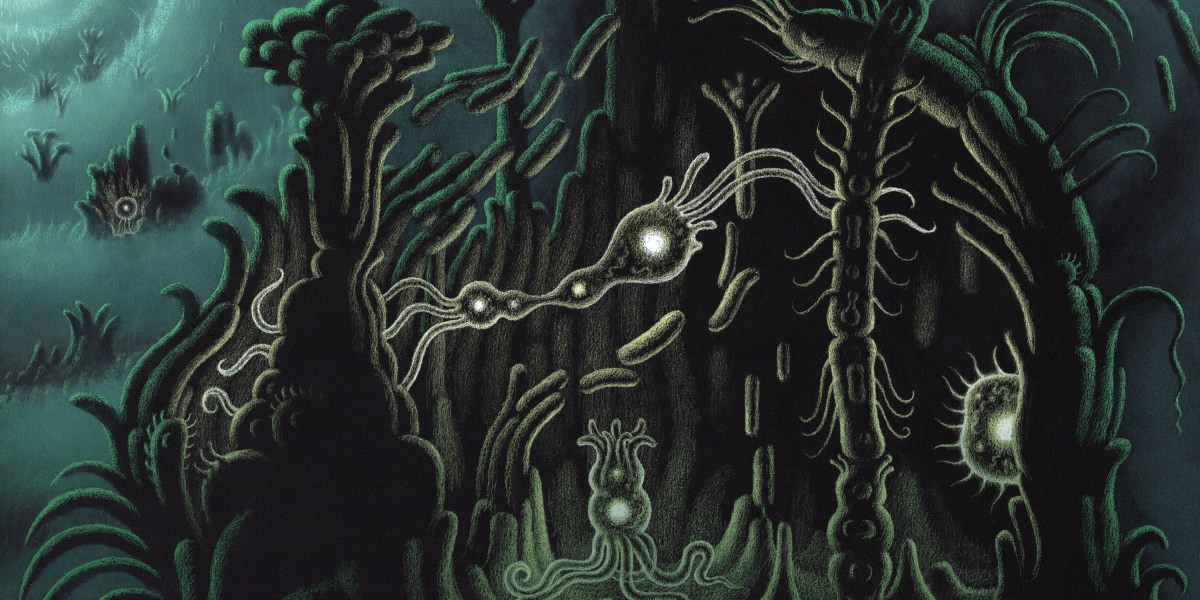

The first step to finding out is to catalogue what microbes we might have lost. To get as close to ancient microbiomes as possible, microbiologists have begun studying multiple Indigenous groups. Two have received the most attention: the Yanomami of the Amazon rainforest and the Hadza, in northern Tanzania.

Researchers have made some startling discoveries already. A study by Sonnenburg and his colleagues, published in July, found that the gut microbiomes of the Hadza appear to include bugs that aren’t seen elsewhere—around 20% of the microbe genomes identified had not been recorded in a global catalogue of over 200,000 such genomes. The researchers found 8.4 million protein families in the guts of the 167 Hadza people they studied. Over half of them had not previously been identified in the human gut.

Plenty of other studies published in the last decade or so have helped build a picture of how the diets and lifestyles of hunter-gatherer societies influence the microbiome, and scientists have speculated on what this means for those living in more industrialized societies. But these revelations have come at a price.

A changing way of life

The Hadza people hunt wild animals and forage for fruit and honey. “We still live the ancient way of life, with arrows and old knives,” says Mangola, who works with the Olanakwe Community Fund to support education and economic projects for the Hadza. Hunters seek out food in the bush, which might include baboons, vervet monkeys, guinea fowl, kudu, porcupines, or dik-dik. Gatherers collect fruits, vegetables, and honey.

Mangola, who has met with multiple scientists over the years and participated in many research projects, has witnessed firsthand the impact of such research on his community. Much of it has been positive. But not all researchers act thoughtfully and ethically, he says, and some have exploited or harmed the community.

One enduring problem, says Mangola, is that scientists have tended to come and study the Hadza without properly explaining their research or their results. They arrive from Europe or the US, accompanied by guides, and collect feces, blood, hair, and other biological samples. Often, the people giving up these samples don’t know what they will be used for, says Mangola. Scientists get their results and publish them without returning to share them. “You tell the world [what you’ve discovered]—why can’t you come back to Tanzania to tell the Hadza?” asks Mangola. “It would bring meaning and excitement to the community,” he says.

Some scientists have talked about the Hadza as if they were living fossils, says Alyssa Crittenden, a nutritional anthropologist and biologist at the University of Nevada in Las Vegas, who has been studying and working with the Hadza for the last two decades.

The Hadza have been described as being “locked in time,” she adds, but characterizations like that don’t reflect reality. She has made many trips to Tanzania and seen for herself how life has changed. Tourists flock to the region. Roads have been built. Charities have helped the Hadza secure land rights. Mangola went abroad for his education: he has a law degree and a master’s from the Indigenous Peoples Law and Policy program at the University of Arizona.

Tech

The Download: a microbiome gold rush, and Eric Schmidt’s election misinformation plan

Published

5 months agoon

12/18/2023By

Drew Simpson

Over the last couple of decades, scientists have come to realize just how important the microbes that crawl all over us are to our health. But some believe our microbiomes are in crisis—casualties of an increasingly sanitized way of life. Disturbances in the collections of microbes we host have been associated with a whole host of diseases, ranging from arthritis to Alzheimer’s.

Some might not be completely gone, though. Scientists believe many might still be hiding inside the intestines of people who don’t live in the polluted, processed environment that most of the rest of us share. They’ve been studying the feces of people like the Yanomami, an Indigenous group in the Amazon, who appear to still have some of the microbes that other people have lost.

But there is a major catch: we don’t know whether those in hunter-gatherer societies really do have “healthier” microbiomes—and if they do, whether the benefits could be shared with others. At the same time, members of the communities being studied are concerned about the risk of what’s called biopiracy—taking natural resources from poorer countries for the benefit of wealthier ones. Read the full story.

—Jessica Hamzelou

Eric Schmidt has a 6-point plan for fighting election misinformation

—by Eric Schmidt, formerly the CEO of Google, and current cofounder of philanthropic initiative Schmidt Futures

The coming year will be one of seismic political shifts. Over 4 billion people will head to the polls in countries including the United States, Taiwan, India, and Indonesia, making 2024 the biggest election year in history.

Tech

Navigating a shifting customer-engagement landscape with generative AI

Published

5 months agoon

12/18/2023By

Drew Simpson

A strategic imperative

Generative AI’s ability to harness customer data in a highly sophisticated manner means enterprises are accelerating plans to invest in and leverage the technology’s capabilities. In a study titled “The Future of Enterprise Data & AI,” Corinium Intelligence and WNS Triange surveyed 100 global C-suite leaders and decision-makers specializing in AI, analytics, and data. Seventy-six percent of the respondents said that their organizations are already using or planning to use generative AI.

According to McKinsey, while generative AI will affect most business functions, “four of them will likely account for 75% of the total annual value it can deliver.” Among these are marketing and sales and customer operations. Yet, despite the technology’s benefits, many leaders are unsure about the right approach to take and mindful of the risks associated with large investments.

Mapping out a generative AI pathway

One of the first challenges organizations need to overcome is senior leadership alignment. “You need the necessary strategy; you need the ability to have the necessary buy-in of people,” says Ayer. “You need to make sure that you’ve got the right use case and business case for each one of them.” In other words, a clearly defined roadmap and precise business objectives are as crucial as understanding whether a process is amenable to the use of generative AI.

The implementation of a generative AI strategy can take time. According to Ayer, business leaders should maintain a realistic perspective on the duration required for formulating a strategy, conduct necessary training across various teams and functions, and identify the areas of value addition. And for any generative AI deployment to work seamlessly, the right data ecosystems must be in place.

Ayer cites WNS Triange’s collaboration with an insurer to create a claims process by leveraging generative AI. Thanks to the new technology, the insurer can immediately assess the severity of a vehicle’s damage from an accident and make a claims recommendation based on the unstructured data provided by the client. “Because this can be immediately assessed by a surveyor and they can reach a recommendation quickly, this instantly improves the insurer’s ability to satisfy their policyholders and reduce the claims processing time,” Ayer explains.

All that, however, would not be possible without data on past claims history, repair costs, transaction data, and other necessary data sets to extract clear value from generative AI analysis. “Be very clear about data sufficiency. Don’t jump into a program where eventually you realize you don’t have the necessary data,” Ayer says.

The benefits of third-party experience

Enterprises are increasingly aware that they must embrace generative AI, but knowing where to begin is another thing. “You start off wanting to make sure you don’t repeat mistakes other people have made,” says Ayer. An external provider can help organizations avoid those mistakes and leverage best practices and frameworks for testing and defining explainability and benchmarks for return on investment (ROI).

Using pre-built solutions by external partners can expedite time to market and increase a generative AI program’s value. These solutions can harness pre-built industry-specific generative AI platforms to accelerate deployment. “Generative AI programs can be extremely complicated,” Ayer points out. “There are a lot of infrastructure requirements, touch points with customers, and internal regulations. Organizations will also have to consider using pre-built solutions to accelerate speed to value. Third-party service providers bring the expertise of having an integrated approach to all these elements.”