Tech

Kapow!

Published

2 years agoon

By

Drew Simpson

Secreted beneath MIT’s Killian Court and accessible only through a subterranean labyrinth of tunnels, a clandestine lab conducts boundary-pushing research, fed by money siphoned from a Department of Defense grant. In these shadowed, high-tech halls, astrophysicist and astronaut Valentina Resnick-Baker, who is experiencing strange phenomena after an encounter with a planet-threatening asteroid, discovers she has the power of plasma fusion.

Resnick-Baker is the buff and brainy heroine of Summit, a 15-issue comic series created and written by Amy Chu ’91. The situations may be fictional, but the science is—broadly—real. (Chu did background research on plasma physics for the series, and when writing about the Batman villain Poison Ivy, she learned the basics of CRISPR so Ivy could deploy it to develop her own plant “kids.”) “The thing that has bothered me for a long time is that a lot of superhero stories are based on complete nonsense,” says Chu, 54. “Every story I do I try to ground in science.”

That a graduate of MIT prefers scientific plausibility to Kryptonite and radioactive spider bites may be the least surprising thing about Chu. At age 42, after a successful career spent largely in conference rooms, this erstwhile management consultant entered her own alternate universe as a comic book writer. First through her publishing startup, Alpha Girl Comics, and now through work for heavyweights like Marvel and DC, Chu is reimagining a traditionally white male medium for girls, Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders, and others who rarely see themselves in its color-saturated panels.

“A lot of superhero stories are based on complete nonsense. Every story I do I try to ground in science.”

Amy Chu

With comics, Chu is pursuing both a market opportunity and a social agenda, the latter familiar to the battle-scarred women of gaming. “All these people are screaming and hollering about comics: that they are dying because girls and women are killing them,” says Chu, referring to well-publicized misogyny directed at female creators and fans. “The future of comics hinges on the ability to get girls as readers.”

Making the team

Chu’s advocacy for women and girls began as advocacy for herself. Her parents, who immigrated from Hong Kong in 1968, moved the family around the country for her father’s positions in nuclear and, later, medical physics. In 1980 they ended up in Iowa City, where Chu balanced nerdy predilections (chess team, Dungeons & Dragons, text-based computer games) with a love of soccer. Her school had only a boys’ team, which she made—but the coach wouldn’t let her play. Chu’s family sued the school district and won.

In 1985 Chu moved to Massachusetts and embarked on a dual-degree program that required her to divide her time between MIT, where she studied architectural design, and Wellesley, where she pursued East Asian studies. But it was at MIT’s Phi Beta Epsilon fraternity that she met her destiny. Chu’s boyfriend at the time was a member there, and the girlfriend of one of his friends had been storing a large box stuffed with comics at the frat. Many were from First Comics, an alternative publisher specializing in spies, adventurers, and science fiction. “I read almost the entire box that summer,” says Chu, who previously had equated comics with superheroes. “It was a revelation.”

That’s the origin story. But Chu’s career in comics was a long way off. At Wellesley she did dabble in publishing, launching a cultural journal to prod the creation of a class in Asian-American studies. And after graduating from Wellesley in 1989, she moved to New York to cofound A. Magazine, a general-interest publication for Asian-American readers. But Chu knew that a startup magazine was unlikely to make enough money to survive, so after about a year she returned to Cambridge to finish her MIT degree. (A. lasted another eight years.)

After senior jobs at several Asian-American nonprofits in New York, Chu spent two and a half years in Hong Kong and Macau. While overseas she worked for billionaire businesswoman Pansy Ho, who owned a PR firm that produced events for luxury brands, and also worked with her family’s business developing tourism in Macau. Ho became a mentor.

Chu returned to the US to attend Harvard Business School and in 1999, MBA in hand, boarded the management-consulting train. Two years at the strategic consultancy Marakon helped her retire some Brobdingnagian student loans. Then Ho asked Chu to assist a few of her biotech investments in the US. That touched off close to a decade of business trips and PowerPoints, with Chu working as an independent consultant for Ho and others. “There was a great need at that time for biotech Red Sonjas,” she says, referring to the flame-haired mercenary about whom she also has written.

By 2010, Chu was burnt out. Not only was her work intense, but she was raising two young children and exhausted from treatment for breast cancer. At the first Harvard Asian-American Alumni Summit, she connected with Georgia Lee, a friend who had engineered a 180-degree turn from consulting to writing and filmmaking. Lee laid out her new vision for a comics publisher targeting girls and women. Back then, female characters in established comics were reduced largely to cleavage and catsuits for the eyes of a presumed male readership.

The paucity of comics created by and for women awoke the sense of unfairness that had driven Chu back in Iowa. “I made the team in soccer,” she says. “I would make the team in comics.”

Becoming a writer

Chu and Lee’s startup, Alpha Girl Comics, debuted with a sci-fi Western by Lee called Meridien City. The founders planned to release work by other women later. As Chu prepared to take on the role of publisher, Lee urged her to learn every aspect of the business. So Chu signed up for a comic writing and editing program created by a former Marvel editor. “That’s where I got hooked,” she says.

Shortly after Alpha Girl released its first title, Lee couldn’t pass up the opportunity to direct a film in Hong Kong. By that time, Chu had written some stories of her own. “The whole thing shifted over to me,” she says. “So I said, I guess I will publish my stuff, with a bunch of artists.” (Like many comic writers, Chu crafts stories and collaborates with artists who draw the panels.)

Though her background doesn’t scream “comics creator,” it actually prepared her well for the work, she says. From the soulless labor of PowerPoint generation during her consulting career, she mastered economy of storytelling. And architectural design, her major at MIT, taught her to optimize space within constraints. (Chu compares fitting a full-blown fight scene into a 10-page comic to fitting a grand piano into a studio apartment: “You have to sacrifice things or it will be a bad experience.”)

For Alpha Girl, Chu wrote and produced two titles. Girls Night Out is a three-volume series that follows the adventures of a woman with dementia and her friends, who abscond from a nursing home. VIP Room is a one-off horror tale about five strangers imprisoned in a mysterious place. But hustling sales at conventions—Alpha Girl’s chief form of distribution—did not pave a path to prosperity. To raise her industry profile and make a little more money, Chu became a pen-for-hire, spinning new adventures for pop-culture icons developed by Marvel, DC Comics, and other publishers.

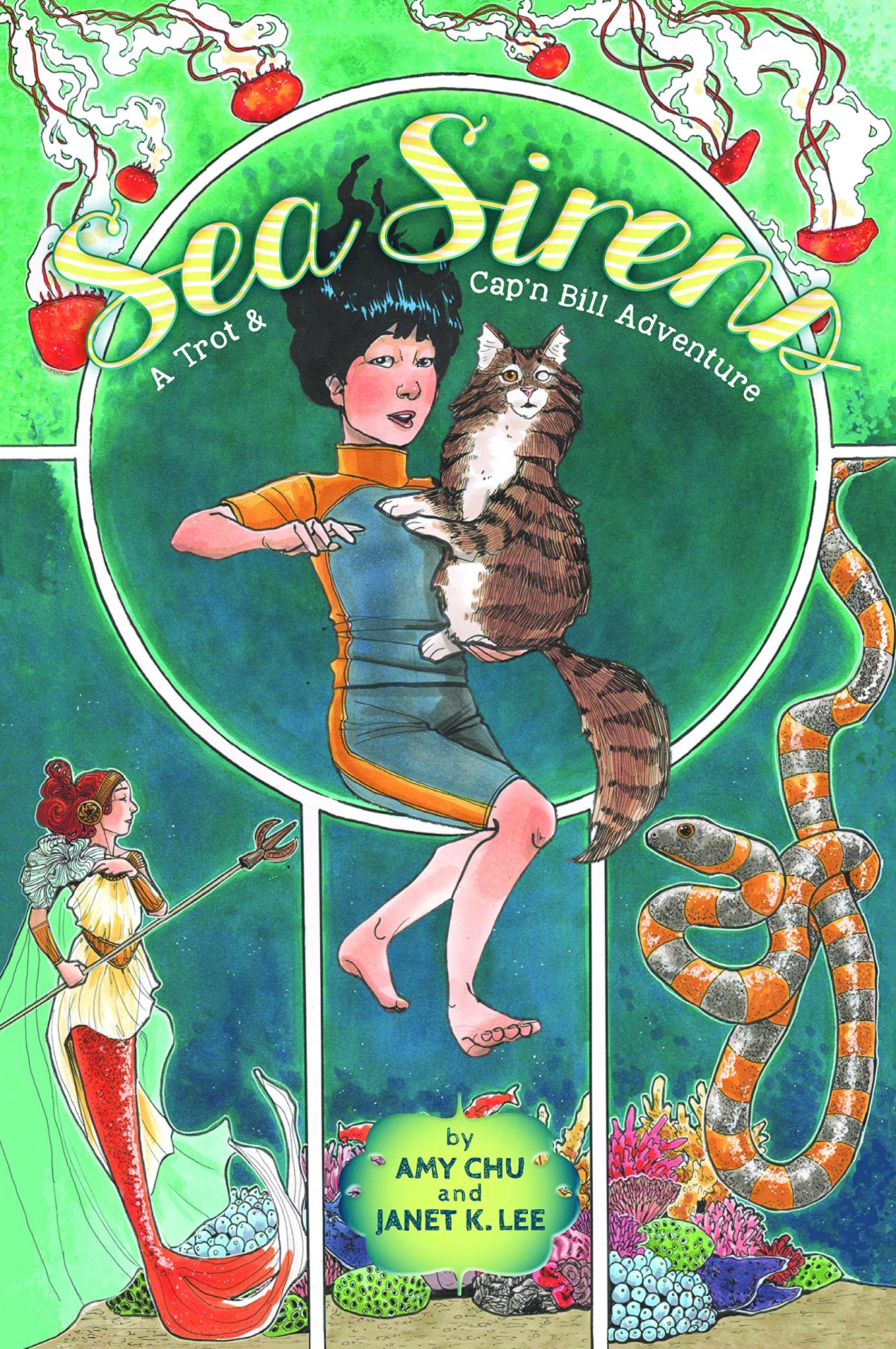

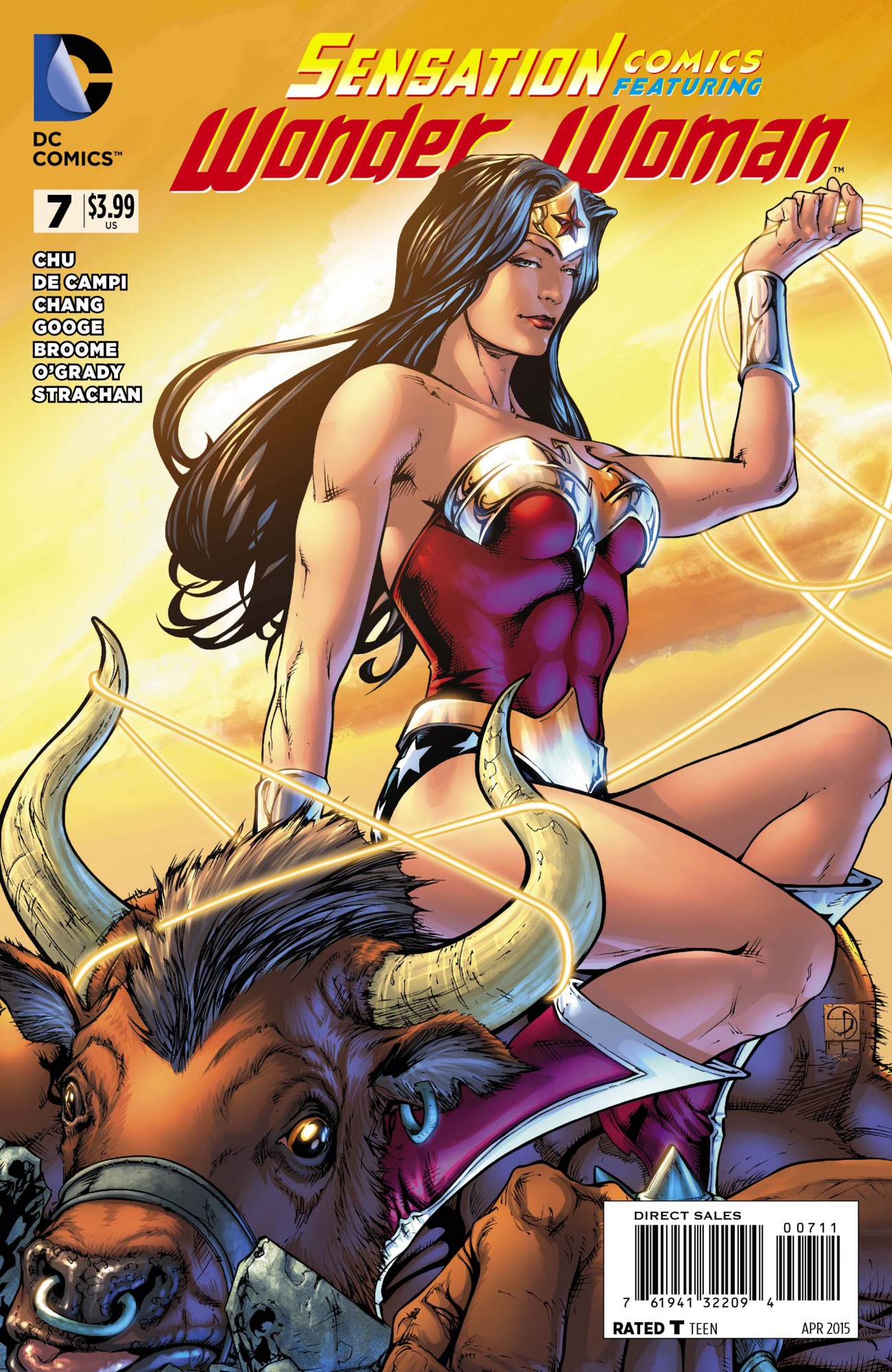

Chu’s decade-long career in comics has included a venture in independent publishing, graphic novels for young readers, and contemporary re-imaginings of the industry’s most iconic characters.

One notable creation was the story arc she developed in 2016 for Poison Ivy, a Batman villain who’d debuted in 1966 as a plant-obsessed eco-terrorist. Chu rethought the character as she produced Ivy’s first solo series, taking a sympathetic approach to her complicated morality. After getting feedback during a Wonder Con panel about the scarcity of Asian-Americans in comics, she added a South Asian male lead, partly inspired by a Jain classmate from MIT. (“Jains are extreme vegetarians, which of course was very interesting to Ivy,” she says.) Comics, says Chu, give her “a platform to increase representation and diversity.”

Comics also provide her with opportunities to get a little silly. In 2016, Chu began writing about the popular character Red Sonja, transplanting the sword-wielding barbarian from a fictional country and epoch to modern-day New York City. A few years later, Dynamite Entertainment and Archie Comics asked her to create a limited-series crossover between Sonja and Riverdale’s favorite female teen frenemies. “I thought, that is so ridiculous I am just going to say no,” says Chu of what ultimately became Red Sonja & Vampirella Meet Betty & Veronica. “Then I thought, if I can do it and make it good, that is a testament to my ability.”

MIT inspiration

Chu soon became a sought-after writer and is often asked to provide a fresh perspective on characters that may have been conceived decades ago. Ideas come from all over, including MIT Technology Review, which Chu calls “grounded in science and forward-thinking.”

The Institute has proffered inspiration in other ways. At a Baltimore Comic Con where she was on a panel, Chu reconnected with Wisdom Coleman ’91. Coleman talked about his experiences as a combat pilot in Afghanistan and the women who served alongside him there. The lives of those women became the basis for Chu’s first Wonder Woman story, about a female pilot who wonders whether her own heroics are in fact the work of the Lady of the Golden Lariat. (They’re not.)

Characters like that female pilot and Resnick-Baker, the astrophysicist-astronaut at the heart of the Summit series, dress as Chu conceived them: like real women doing real work. Characters that Chu did not create, by contrast, often are rendered in the hypersexualized style she detests. There’s not much she can do about it. “A lot is dependent on the editor and the editor’s selection of the artist,” she says. One sign of progress, she observes, is the less exploitative approach of comic books targeting young audiences or produced by a growing cadre of female editors.

Chu sometimes will push back, as when an artist working on one of her books depicted Poison Ivy in a thong. “I literally was on a call where I walked them through the Victoria’s Secret catalogue and told them what would be appropriate,” she says. “Somewhere between bikini and boy shorts is what I was imagining.” (The artist made the change.)

Today Chu gets so much work from mainstream publishers that she lacks time for Alpha Girl, which has not released a new title in several years. (Lee went on to write for television, notably for the Syfy and Amazon Prime Video series The Expanse.) She wants to revisit Alpha Girl, but “I keep getting stuff where I am like, I have got to write that because it is pretty cool,” she says. “Green Hornet? Yeah, I want to write Green Hornet! Wonder Woman? Of course!”

Chu also has ventured into more traditional publishing. In 2019 and 2020 Viking released two volumes of Sea Sirens, a graphic novel for middle graders created by Chu and her friend Janet K. Lee, the Eisner Award–winning illustrator. Adapted from a 1911 underwater fantasy by Wizard of Oz author L. Frank Baum, Chu and Lee’s updated version reimagines the heroine, Trot, as a Vietnamese-American girl in Southern California. Her adult male companion is now a talking cat. “The idea of a young girl wandering around with a strange older man having adventures raises a lot of questions these days,” says Chu.

There are other demands on Chu’s time. Three years ago, she was recruited to write two episodes for the Netflix series DOTA: Dragon’s Blood, based on the popular video game. (A second, undisclosed Netflix program is in the works.) She’s also starting work on a comic series based on the Borderlands video games. On a different track, another MIT friend, Norman Chen ’88, who now runs the Asian American Foundation, recruited Chu to produce an overview of Asian-American history for grade-school students.

If Chu eventually does revive Alpha Girl, she may enjoy a new generation of readers and contributors. About 10 years ago the Girl Scouts created a Comic Artist badge, and Chu was flooded with requests to address the troops. “In a few years, a lot more women will have had this exposure,” she says. “If they are anything like me, they will get hooked.”

You may like

Tech

The hunter-gatherer groups at the heart of a microbiome gold rush

Published

5 months agoon

12/19/2023By

Drew Simpson

The first step to finding out is to catalogue what microbes we might have lost. To get as close to ancient microbiomes as possible, microbiologists have begun studying multiple Indigenous groups. Two have received the most attention: the Yanomami of the Amazon rainforest and the Hadza, in northern Tanzania.

Researchers have made some startling discoveries already. A study by Sonnenburg and his colleagues, published in July, found that the gut microbiomes of the Hadza appear to include bugs that aren’t seen elsewhere—around 20% of the microbe genomes identified had not been recorded in a global catalogue of over 200,000 such genomes. The researchers found 8.4 million protein families in the guts of the 167 Hadza people they studied. Over half of them had not previously been identified in the human gut.

Plenty of other studies published in the last decade or so have helped build a picture of how the diets and lifestyles of hunter-gatherer societies influence the microbiome, and scientists have speculated on what this means for those living in more industrialized societies. But these revelations have come at a price.

A changing way of life

The Hadza people hunt wild animals and forage for fruit and honey. “We still live the ancient way of life, with arrows and old knives,” says Mangola, who works with the Olanakwe Community Fund to support education and economic projects for the Hadza. Hunters seek out food in the bush, which might include baboons, vervet monkeys, guinea fowl, kudu, porcupines, or dik-dik. Gatherers collect fruits, vegetables, and honey.

Mangola, who has met with multiple scientists over the years and participated in many research projects, has witnessed firsthand the impact of such research on his community. Much of it has been positive. But not all researchers act thoughtfully and ethically, he says, and some have exploited or harmed the community.

One enduring problem, says Mangola, is that scientists have tended to come and study the Hadza without properly explaining their research or their results. They arrive from Europe or the US, accompanied by guides, and collect feces, blood, hair, and other biological samples. Often, the people giving up these samples don’t know what they will be used for, says Mangola. Scientists get their results and publish them without returning to share them. “You tell the world [what you’ve discovered]—why can’t you come back to Tanzania to tell the Hadza?” asks Mangola. “It would bring meaning and excitement to the community,” he says.

Some scientists have talked about the Hadza as if they were living fossils, says Alyssa Crittenden, a nutritional anthropologist and biologist at the University of Nevada in Las Vegas, who has been studying and working with the Hadza for the last two decades.

The Hadza have been described as being “locked in time,” she adds, but characterizations like that don’t reflect reality. She has made many trips to Tanzania and seen for herself how life has changed. Tourists flock to the region. Roads have been built. Charities have helped the Hadza secure land rights. Mangola went abroad for his education: he has a law degree and a master’s from the Indigenous Peoples Law and Policy program at the University of Arizona.

Tech

The Download: a microbiome gold rush, and Eric Schmidt’s election misinformation plan

Published

5 months agoon

12/18/2023By

Drew Simpson

Over the last couple of decades, scientists have come to realize just how important the microbes that crawl all over us are to our health. But some believe our microbiomes are in crisis—casualties of an increasingly sanitized way of life. Disturbances in the collections of microbes we host have been associated with a whole host of diseases, ranging from arthritis to Alzheimer’s.

Some might not be completely gone, though. Scientists believe many might still be hiding inside the intestines of people who don’t live in the polluted, processed environment that most of the rest of us share. They’ve been studying the feces of people like the Yanomami, an Indigenous group in the Amazon, who appear to still have some of the microbes that other people have lost.

But there is a major catch: we don’t know whether those in hunter-gatherer societies really do have “healthier” microbiomes—and if they do, whether the benefits could be shared with others. At the same time, members of the communities being studied are concerned about the risk of what’s called biopiracy—taking natural resources from poorer countries for the benefit of wealthier ones. Read the full story.

—Jessica Hamzelou

Eric Schmidt has a 6-point plan for fighting election misinformation

—by Eric Schmidt, formerly the CEO of Google, and current cofounder of philanthropic initiative Schmidt Futures

The coming year will be one of seismic political shifts. Over 4 billion people will head to the polls in countries including the United States, Taiwan, India, and Indonesia, making 2024 the biggest election year in history.

Tech

Navigating a shifting customer-engagement landscape with generative AI

Published

5 months agoon

12/18/2023By

Drew Simpson

A strategic imperative

Generative AI’s ability to harness customer data in a highly sophisticated manner means enterprises are accelerating plans to invest in and leverage the technology’s capabilities. In a study titled “The Future of Enterprise Data & AI,” Corinium Intelligence and WNS Triange surveyed 100 global C-suite leaders and decision-makers specializing in AI, analytics, and data. Seventy-six percent of the respondents said that their organizations are already using or planning to use generative AI.

According to McKinsey, while generative AI will affect most business functions, “four of them will likely account for 75% of the total annual value it can deliver.” Among these are marketing and sales and customer operations. Yet, despite the technology’s benefits, many leaders are unsure about the right approach to take and mindful of the risks associated with large investments.

Mapping out a generative AI pathway

One of the first challenges organizations need to overcome is senior leadership alignment. “You need the necessary strategy; you need the ability to have the necessary buy-in of people,” says Ayer. “You need to make sure that you’ve got the right use case and business case for each one of them.” In other words, a clearly defined roadmap and precise business objectives are as crucial as understanding whether a process is amenable to the use of generative AI.

The implementation of a generative AI strategy can take time. According to Ayer, business leaders should maintain a realistic perspective on the duration required for formulating a strategy, conduct necessary training across various teams and functions, and identify the areas of value addition. And for any generative AI deployment to work seamlessly, the right data ecosystems must be in place.

Ayer cites WNS Triange’s collaboration with an insurer to create a claims process by leveraging generative AI. Thanks to the new technology, the insurer can immediately assess the severity of a vehicle’s damage from an accident and make a claims recommendation based on the unstructured data provided by the client. “Because this can be immediately assessed by a surveyor and they can reach a recommendation quickly, this instantly improves the insurer’s ability to satisfy their policyholders and reduce the claims processing time,” Ayer explains.

All that, however, would not be possible without data on past claims history, repair costs, transaction data, and other necessary data sets to extract clear value from generative AI analysis. “Be very clear about data sufficiency. Don’t jump into a program where eventually you realize you don’t have the necessary data,” Ayer says.

The benefits of third-party experience

Enterprises are increasingly aware that they must embrace generative AI, but knowing where to begin is another thing. “You start off wanting to make sure you don’t repeat mistakes other people have made,” says Ayer. An external provider can help organizations avoid those mistakes and leverage best practices and frameworks for testing and defining explainability and benchmarks for return on investment (ROI).

Using pre-built solutions by external partners can expedite time to market and increase a generative AI program’s value. These solutions can harness pre-built industry-specific generative AI platforms to accelerate deployment. “Generative AI programs can be extremely complicated,” Ayer points out. “There are a lot of infrastructure requirements, touch points with customers, and internal regulations. Organizations will also have to consider using pre-built solutions to accelerate speed to value. Third-party service providers bring the expertise of having an integrated approach to all these elements.”